Isaac Rosenberg, War Poet of Trauma

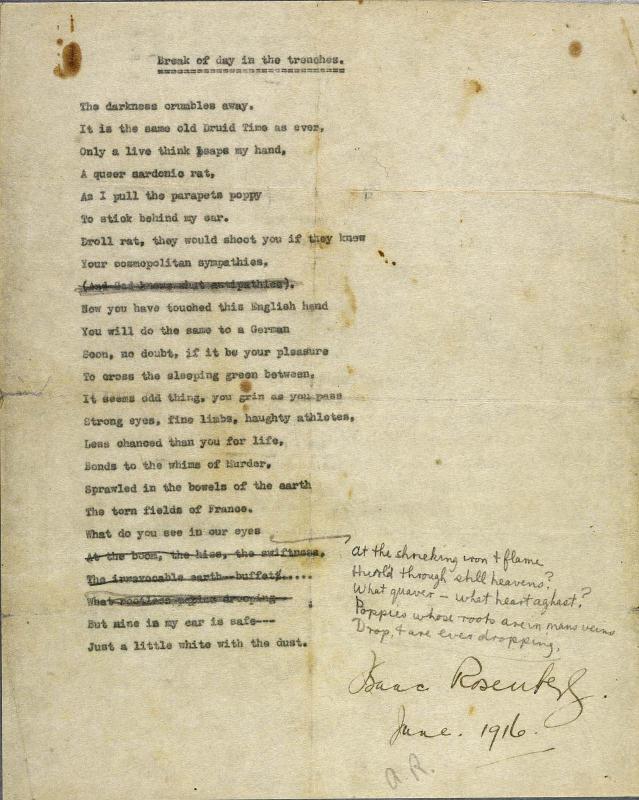

In “Break of Day in the Trenches,” Rosenberg describes a “queer sardonic rat” leaping over his hand as he pulls “the parapet’s poppy / to stick behind my ear” (4-6). Despite the threat of disease and harm which most rats posed in the trenches, this rat is deserting the trench for German lines. Rosenberg addresses the rat directly as he ponders how the young men in the trench are less likely to survive the war than the rat, who may come and go as he pleases.

As a private on the front lines of the Western Front, Rosenberg was injured before he was reassigned to a works battalion. This experience is reflected in his poem “Dead Man’s Dump,” which is written from the point of view of a soldier going out on a limber, or carriage, to set up barbed wire in No-Man’s Land. As the man drives the carriage, “The wheels lurched over sprawled dead / But pained them not, though their bones crunched,” providing a graphic depiction of the dead who still seem to suffer in No-Man’s Land, despite their deceased condition (7-8).

To make matters worse, the dying are among the dead in No-Man’s Land, slipping from stretchers, or already almost dead, mingling with the corpses ground beneath the wheels of the limber: “We heard his weak scream / We heard his very last sound, / And our wheels grazed his dead face” (84-86). The limber must lay out the barbed wire to protect the men who are still living, so the wheels continue their grisly procession. How long, Rosenberg seems to ask, until the living soldiers join the corpses in No-Man’s Land? This sense of total despair offers the reader a sense of what it may have felt like to live through the rapidly traumatizing effects of war.